Wildfires Threaten to Contaminate Water

Data from the National Interagency Fire Center (NIFC) indicates wildfires are burning more than twice the area than they did in the 1980s and 1990s. These disasters harm and displace thousands of people annually, and damage or destroy property and the environment. Even when fires are put out, contamination from ash and melted or burned debris can contaminate drinking water and hamper rebuilding efforts.

After the Camp Fire in California, area residents contacted drinking water expert Andrew Whelton, an associate professor of civil engineering at Purdue University to ask for advice. He said many “took showers in potentially contaminated water and felt nauseous or lightheaded.”

One of the deadliest and most destructive wildfires in California’s history, the Camp Fire burned 153,000 acres. Local officials then uncovered widespread drinking water chemical contamination in water distribution networks, with volatile organic compounds such as benzene exceeding state and federal limits in public water supplies. The contamination was isolated in water networks and was not found in source water, making it clear that the cause was melted plastic pipes and components within the water systems. The issue left residents without access to safe drinking water for years and required millions of dollars in repairs.

Santa Rosa suffered similar impacts from wildfire damage. “The combustion, the burning, the melting of various plastic components in our distribution system gave off constituents that got into the water system,” said Bennett Horenstein, Santa Rosa’s director of water. “We’re finding a very broad spectrum of chemicals that were released as the plastic burned, with benzene being the leading contaminant and the leading issue in terms of public health exposure.”

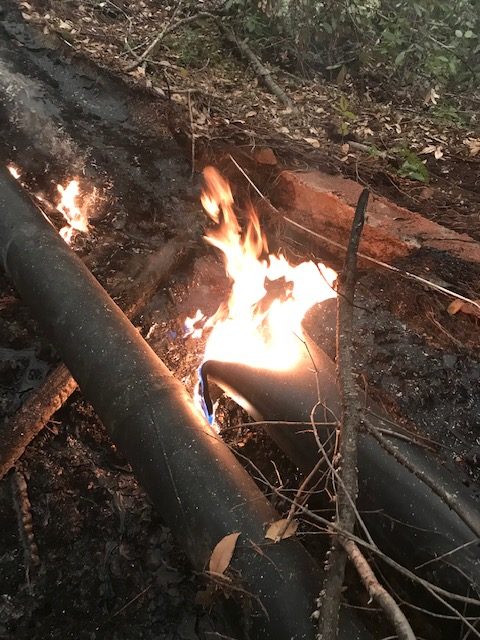

The San Francisco Chronicle reported nearly identical issues in Boulder Creek, where system failures may have allowed harmful chemicals to enter the water. In this case, several miles of HDPE pipe melted, making the water unsafe for consumption. The pipe required full replacement at a cost of roughly 10 million dollars. A similar incident in San Lorenzo, California, left hundreds without access to clean drinking water after a fire burned the entirety of the city’s 7.5-mile water pipeline.

Residents of Detroit, Oregon, returned home after the Lionshead Fire destroyed roughly 250 homes and businesses. With 70 percent of public buildings in Detroit burned to the ground, community members knew they were in for a long rebuilding process. The destruction the area’s water treatment plant, however, may well leave the town with health and safety concerns for up to 10 years as officials monitor drinking water for carcinogenic compounds like benzene.

“Experience from (California) wildfires has shown that VOCs, particularly benzene, can be found in water systems that both lost pressure and lost structure due to fire, causing plastic pipes to melt or off-gas contaminants,” said Oregon Health Authority spokesperson Jonathan Modie in an email to the Statesman Journal.

Piping, Wildfires, & Water Quality

The relationship between piping systems, wildfires, and unsafe drinking water has become more visible in the past decade, raising concerns on the role of piping materials as a primary source of water contamination. Whelton’s 2020 study on contamination following wildfires in Paradise and Santa Rosa provides insight on the relationship between piping, wildfires, and water quality. One key finding: plastic piping materials like polyvinyl chloride (PVC), high-density polyethylene (HDPE), and polybutylene (PB) were present in all water distribution networks affected by the fires. “Communities need to recognize this vulnerability,” says Whelton. “Dangerous chemicals can leach from inside water systems for months after a fire.”

During wildfire events, such systems begin “cooking plastic underground,” releasing volatile organic compounds that are inherent in their material composition into the water – as they cannot escape into the air. Volatile organic compounds such as benzene, toluene, naphthalene, and vinyl chloride are all generated as a result of the thermal degradation of plastic pipes like PVC. Whelton found benzene exceeded exposure limits in water, as did a range of other volatile organic compounds (VOCs), including dichloromethane, naphthalene, styrene, tert-butyl alcohol, toluene, and vinyl chloride. All these chemicals pose serious threats to human health when consumed.

Material selection for water distribution piping represents an essential element in reducing risks of water contamination in areas vulnerable to wildfires. As wildfires burn hotter and longer, areas vulnerable to wildfires will need to take action to prevent drinking water contamination disasters. Whelton’s team made several recommendations for local and regional officials to consider:

- Increase research to assess water contamination in post-wildfire scenarios

- Employ rapid, standardized, and widespread testing to identify sources of contamination, piping assets at risk, and transportation mechanisms of contamination

- Issue mandatory “Do Not Use” water orders to protect public health after wildfires

- Define policy priorities before a disaster to facilitate utility and public health response

- Give clear, data-based recommendations to protect residents’ health… and safeguard piping infrastructure.